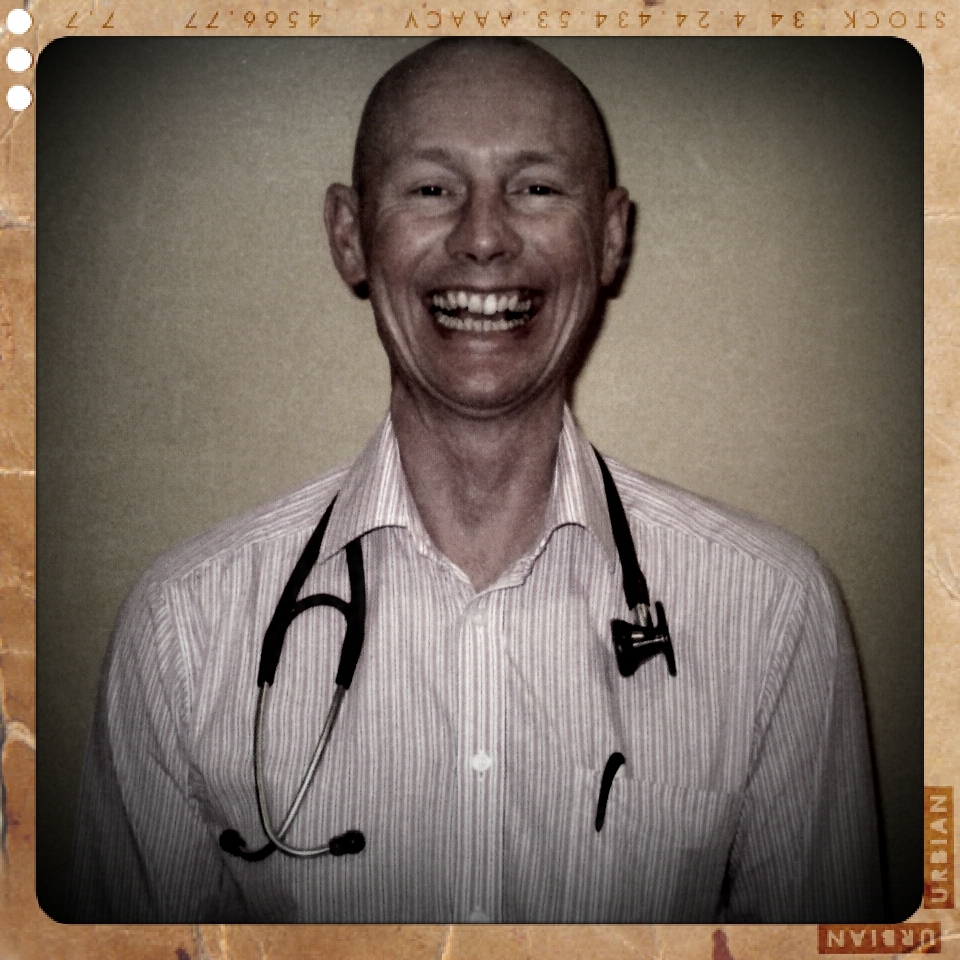

This is Jörn Cann.

He was my ward doctor at the haematology unit where I was treated for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2006.

I was intrigued by him before I even met him. My consultant whispered to me that Jörn had himself been treated for blood cancer, the related but different Hodgkin’s lymphoma. ‘He’ll know what you’re about to go through,’ she said.

Walking round a corner to the ward where he worked, we bumped into him filling a doorway and shout-sharing a joke with some nurses. He shook my hand, put his arm around me, then swore at me for being a Chelsea fan.

That was Jörn in microcosm: warm, intimate and abrupt. I never knew a person who stood on less ceremony.

Readers who knew Jörn will already know why I am writing about him in the past tense. He died suddenly and unexpectedly from peritonitis in September 2011. He was 43.

I have called this piece ‘The art of Jörn Cann’ not because he ran round the wards sketching us while we sat on our drips but because he cared. Of course he did, you might say: he was paid to. Well, yes, up to a point.

The art I am referring to is based on an idea of Seth Godin’s from his book The Icarus Deception. There he talks about ‘art’ as a vital force of connection and transformation as the old industrial model of production crumbles around us. It’s the difference, he says, between a doctor giving you results from a blood test and actually sitting down with you to explain its implications.

That’s art. It disregards the training manual and is mindful of the human stories of others, whatever the risk involved. That was what Jörn gave to patients each day of his life on the haematology wards. It is worth remembering that there are thousands like him working in the NHS, whose stories are not normally represented in the discourse surrounding it, so often reduced as it is to numbers and statistics.

Half way through my treatment, when it looked as though my infusions of chemotherapy were not working, it was Jörn who plopped himself on my bed and without losing eye contact explained: ‘If you’re given a shit pack of cards, those are the ones you play with.’ This is one of the great lessons anyone has taught me about life, creativity, and making the most of what is front of you, ever.

Then he told me he had been treated for his own cancer, on an off, since he was 16.

He didn’t need to say it, and had not been asked to, but he did: ‘And look at me. I’m still here.’ He relapsed a week later.

Even though I now only visit the unit once a year, I miss Jörn more than I can say.

I saw him for the last time in a Lidl supermarket of all places. He greeted me as though his day had been building up to this one special moment. We swapped plans for future projects and stories of our families, followed by a brief but incisive dissection of Arsenal’s current form. That was a kind of art, too. Most doctors you see outside of hospital premises run for cover if they see you.

Even though the circumstances of our relationship were grim, I am deeply proud to have known him. These are some of the reasons Love for Now is dedicated to his memory.

An earlier version of this post appeared on 19 June, 2013

A beautiful tribute…and what a beautiful face he has.

As ever,

Molly

LikeLike

I always enjoy your poignant respectful and delicately woven posts about Jorn. Thanks again for reminding me of the wonders of humanity.

LikeLike